Abstract

For more than 70 years calcium hydroxide has played a major role in endodontic therapy, although many of its functions are now being taken over by the recently introduced material MTA. Calcium hydroxide may be used to preserve the vital pulp if infection and bleeding are controlled; to repair root fractures, perforations, open apices and root resorptions. Endo-perio lesions are complex and the correct diagnosis is essential if treatment is to be successful. However, root canal treatment will always be the first phase in treating such lesions.

Calcium hydroxide was originally introduced to the field of endodontics by Herman ( 1 ) in 1930 as a pulp-capping agent, but its uses today are widespread in endodontic therapy. It is the most commonly used dressing for treatment of the vital pulp. It also plays a major role as an intervisit dressing in the disinfection of the root canal system.

Mode of action

A calcified barrier may be induced when calcium hydroxide is used as a pulp-capping agent or placed in the root canal in contact with healthy pulpal or periodontal tissue. Because of the high pH of the material, up to 12.5, a superficial layer of necrosis occurs in the pulp to a depth of up to 2 mm. Beyond this layer only a mild inflammatory response is seen, and providing the operating field was kept free of bacteria when the material was placed, a hard tissue barrier may be formed. However, the calcium ions that form the barrier are derived entirely from the bloodstream and not from the calcium hydroxide.( 2 ) The hydroxyl group is considered to be the most important component of calcium hydroxide as it provides an alkaline environment which encourages repair and active calcification. The alkaline pH induced not only neutralises lactic acid from the osteoclasts, thus preventing a dissolution of the mineral components of dentine, but could also activate alkaline phosphatases which play an important role in hard tissue formation. The calcified material which is produced appears to be the product of both odontoblasts and connective tissue cells and may be termed osteodentine. The barrier, which is composed of osteodentine, is not always complete and is porous.

In external resorption, the cementum layer is lost from a portion of the root surface, which allows communication through the dentinal tubules between the root canal and the periodontal tissues. It has been shown that the dis-association coefficient of calcium hydroxide of 0.17 permits a slow, controlled release of both calcium and hydroxyl ions which can diffuse through dentinal tubules. Tronstad et al. demonstrated that untreated teeth with pulpal necrosis had a pH of 6.0 to 7.4 in the pulp dentine and periodontal ligament, whereas, after calcium hydroxide had been placed in the canals, the teeth showed a pH range in the peripheral dentine of 7.4 to 9.6.3

Tronstad et al. suggest that calcium hydroxide may have other actions; these include, for example, arresting inflammatory root resorption and stimulation of healing.( 3 ) It also has a bactericidal effect and will denature proteins found in the root canal, thereby making them less toxic. Finally, calcium ions are an integral part of the immunological reaction and may activate the calcium-dependent adenosine triphosphatase reaction associated with hard tissue formation.

Presentation

Delain Calcium Hydroxide Paste Kit is the best ready to use presentation easy and safe for the treatment. Because of the antibacterial effect of calcium hydroxide, it is not necessary to add a germicide ( Iodoform in Vitapex from Morita ). The advantages of using calcium hydroxide in this Delian presentation form are that the best consistency and a pH of about 12 is achieved, which is higher than that of other brands.

Clinical uses and techniques

Clinical uses and techniques

The clinical situations where calcium hydroxide may be used in endodontics are discussed below and the techniques described. The method of application of calcium hydroxide to tissue is important if the maximum benefit is to be gained. When performing pulp capping, pulpotomy or treatment to an open apex in a pulpless tooth, the exposed tissue should be cleaned thoroughly, any haemorrhage arrested by irrigation with sterile saline and the use of sterile cotton wool pledgets. The calcium hydroxide should be placed gently directly on to the tissue, with no debris or blood intervening. A calcium hydroxide cement may be applied to protect the pulp in a deep cavity as discussed later.

Routine canal medication

The indications for intervisit dressing of the root canal with calcium hydroxide have been considered. There are two methods of inserting calcium hydroxide paste into the root canal, the object being to fill the root canal completely with calcium hydroxide so that it is in contact with healthy tissue. Care should be taken to prevent the extrusion of paste into the periapical tissues, although if this does occur healing will not be seriously affected.

The root canal system is first prepared and then dried. A spiral root canal filler is selected and passively tried in the canal. It must be a loose fit in the canal over its entire length, or fracture may occur, as seen in Figure 2. The working length of the canal should be marked on the shank with either marking paste or a rubber stop. The author prefers the blade type of filler as these are less prone to fracture.

Figure 2: Spiral root fillers are prone to fracture if their passive fit in the root canal has not been verified before use

Ready to use Delian Calcium Hydroxide Paste in 1 x 2g Syringe with Application Tip

Ready to use Delian Calcium Hydroxide Paste in 1 x 2g Syringe with Application Tip

The ready to use material is esay to apply due to the perfect shaped application tips pr may be applied be applied using a spiral root canal filler as described earlier, however most practitioners prefer to use the Delian application tips The material is extruded out of the syringe directly deep in the canal. A large paper point may aga in be used to condense the material further, and absorb excess water making the procedure easier and the filling more dense

Figure 3: A paper point may be used to condense the calcium hydroxide in the canal and remove excess moisture

Of utmost importance in endodontics is the temporary coronal seal which prevents leakage and (re)contamination of the canal system. Intermediate Delian restorative material (IRM), or Delian glass-ionomer cement are useful for periods of over 7–10 days; for shorter periods, Delian zinc oxide, Delian Provi Classics, Delian MTA or other proprietary material may be used

Of utmost importance in endodontics is the temporary coronal seal which prevents leakage and (re)contamination of the canal system. Intermediate Delian restorative material (IRM), or Delian glass-ionomer cement are useful for periods of over 7–10 days; for shorter periods, Delian zinc oxide, Delian Provi Classics, Delian MTA or other proprietary material may be used

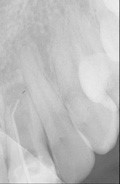

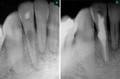

Radiographic appearance due to Barium Sulpate content

A root canal filled with calcium hydroxide should appear on a radiograph as if it were completely sclerosed, as in Figure 4. The material is prone to dissolution, which would appear on a radiograph as voids in the canal. In the past, the addition of more radiopaque agents such as barium sulphate has been recommended. As these materials may be resorbed more slowly than the calcium hydroxide a false picture may be given.

Any part of the canal not filled with the paste appears as a void

Any part of the canal not filled with the paste appears as a void

Indirect pulp capping

The treatment of the deep carious lesion which has not yet involved the pulp has for some time been the subject of intense debate. Some researchers recommend the use of a calcium hydroxide lining to stimulate odontoblasts and increase dentine formation.4, 5 Other workers have claimed that this does not occur.6, 7 Some workers still recommend that infected carious dentine is removed but a layer of softened sterile dentine may be left over the intact vital pulp.8 Most endodontic texts, (for example, see References 9 and 10) recommend that all softened dentine should be removed and the pulp dealt with accordingly.

There is still controversy, however, over the correct treatment of a deep, caries free, cavity, lying close to the pulp. As alluded to in Part 1, the essential treatment is to ensure that there can be no bacterial contamination of the pulp via the exposed dentine tubules.This may be achieved by either a lining of glass-ionomer cement, or the use of an acid-etched dentine bonding system. Some workers have recommended washing the cavity with sodium hypochlorite to further disinfect the dentine surface, and this seems an eminently sensible suggestion. Until further research provides conclusive evidence for or against, however, the use of an indirect pulp cap of calcium hydroxide is recommended in these situations. The calcium hydroxide cement provides a bactericidal effect on any remaining bacteria and may encourage the formation of secondary dentine and of a dentine bridge. It is certainly no longer considered necessary to reopen the cavity at a later date to confirm healing.

Direct pulp capping

Direct pulp capping

The aim of direct pulp capping is to protect the vital pulp which has been exposed during cavity preparation, either through caries or trauma. The most important consideration in obtaining success is that the pulp tissue remains uncontaminated. In deep cavities, when an exposure may be anticipated, all caries should be removed before approaching the pulpal aspect of the cavity floor. If an exposure of the pulp occurs in a carious field the chances of successful pulp capping are severely compromised. A rubber dam should be applied as soon as pulp capping is proposed. The pulp should be symptom-free and uninfected, and the exposure should be small. Before commencing large restorations in suspicious teeth it may be prudent to test the vitality of the tooth with an electronic pulp tester, and also to expose a radiograph to ensure that there is no evidence of pulpal or periapical pathology. The radiograph may in fact be more valuable, as misleading results may occur when using an electric pulp tester on compromised multirooted teeth.

If the above criteria have been met and pulp capping is indicated, the cavity should be cleaned thoroughly, ideally with sodium hypochlorite solution, and pulpal haemorrhage arrested with sterile cotton pledgets. Persistent bleeding indicates an inflamed pulp, which may not respond to treatment. After placing the calcium hydroxide, the area must be sealed against bacterial ingress, preferably with a glass-ionomer lining.

Partial pulpotomy

Although the technique of pulpotomy is indicated for immature teeth with open apices, as described in Part 10, it cannot be recommended routinely in mature teeth. However, the technique of partial pulpotomy (a procedure between pulp capping and pulpotomy) was introduced by Cvek and has been shown to be very successful in the treatment of traumatically exposed pulps.12, 13 The exposed pulp and surrounding dentine is removed under rubber dam isolation with a high-speed diamond drill and copious irrigation using sterile saline, to a depth of about 2 mm. Haemostasis is achieved and the wound dressed with a non-setting calcium hydroxide paste, either powder and sterile saline or a proprietory paste. The cavity is sealed with a suitable lining, such as resin-modified glass-ionomer cement, and restored conventionally. The tooth should be carefully monitored.

Mineral trioxide aggregate

Although the majority of practitioners will use calcium hydroxide routinely and effectively for pulp capping and various repairs to the root, Delian Mineral trioxide aggregate (MTA) is increasingly used in specialist and some general practices. The material is described briefly , and the application discussed. Early research as a root-end filling material showed unparalleled results, and workers have since reported similar success in other endodontic procedures, with no resulting inflammation, and deposition of cementum over the restorative material. Delian MTA can be used in place of hard-setting calcium hydroxide in all these pulp-capping procedures.

Root-end induction (apexification)

The cases in which partial or total closure of an open apex can be achieved are:

vital radicular pulp in an immature tooth pulpotomy

pulpless immature tooth with or without a periapical radiolucent area.

The success of closure is not related to the age of the patient. It is not possible to determine whether there would be continued root growth to form a normal root apex or merely the formation of a calcific barrier across the apical end of the root. The mode of healing would probably be related to the severity and duration of the periapical inflammation and the consequent survival of elements of Hertwig’s sheath.

Inducing apical closure may take anything from 6 to 18 months or occasionally longer. It is necessary to change the calcium hydroxide during treatment; the suggested procedure is given below:

First visit — Thoroughly clean and prepare the root canal. Fill with calcium hydroxide.

Second visit — 2 to 4 weeks later, remove the calcium hydroxide dressing with hand instruments and copious irrigation. Care should be taken not to disturb the periapical tissue. The root canal is dried and refilled with calcium hydroxide.

Third visit — 6 months later, a periapical radiograph is taken and root filled if closure is complete. This may be checked by removing the calcium hydroxide and tapping with a paper point against the barrier. Repeat the calcium hydroxide dressing if necessary.

Fourth visit — After a further 6 months another periapical radiograph is taken, and the tooth root-filled if closure is complete. If the barrier is still incomplete the calcium hydroxide dressing is repeated.

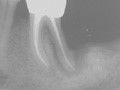

Fifth visit — This should take place 3 to 6 months later. The majority of root closures will have been completed by this time (Fig. 5).

Figure 5: A calcific barrier is evident following calcium hydroxide therapy in a case with an open apex

Once again, however, reference must be made to the increasing use of Delian MTA for root-end closure and other such endodontic procedures.

Once again, however, reference must be made to the increasing use of Delian MTA for root-end closure and other such endodontic procedures.

Horizontal fractures

Horizontal fractures

Horizontal fractures of the root may be treated, provided the fracture lies within the alveolar bone and does not communicate with the oral cavity. The blood supply may have been interrupted at the fracture site only, so that the apical fragment remains vital. In these cases, the coronal portion of the root can be treated as an open apex. Cvek states that healing with a calcific barrier can be achieved using calcium hydroxide.15

Iatrogenic perforations

Iatrogenic perforations are caused by an instrument breaching the apex or wall of the root canal; probably the most common occurrence is during the preparation of a post space (Fig. 6). Partial or complete closure by hard tissue may be induced with calcium hydroxide, provided the perforation is not too large, lies within the crestal bone and does not communicate with the oral cavity. Treatment should begin as soon as possible, adopting the same procedure as for root-end induction. Closure of perforations using calcium hydroxide takes considerably longer than root-end induction in most cases. An alternative technique, if the perforation can be visualised with the use of a surgical microscope, would be direct repair with mineral trioxide aggregate.

Figure 6: The mesial wall of the root canal at tooth UL1 (21) has been perforated during post space preparation, causing a lateral periodontitis

If foreign bodies in the form of root-filling materials, cements or separated instruments have been extruded into the tissues, healing with calcium hydroxide is unlikely to occur and a surgical approach is recommended (Part 11).

If foreign bodies in the form of root-filling materials, cements or separated instruments have been extruded into the tissues, healing with calcium hydroxide is unlikely to occur and a surgical approach is recommended (Part 11).

Root Resorption

Several different types of resorption are recognised: some are isolated to one tooth and slow spreading, others are rapid, aggressive and may involve several teeth. Resorption is initiated either from within the pulp, giving rise to internal resorption, or from outside the tooth, where it is termed external resorption.

The aetiology of resorption has been described by Tronstad who also presented a new classification.18 In Tronstad’s view, the permanent teeth are not normally resorbed, the mineralised tissues are protected by predentine and odontoblasts in the root canal and by precementum and cementoblasts on the root surface. If the predentine or precementum becomes mineralised, or, in the case of the precementum, is mechanically damaged or scraped off, multinucleated cells colonise the mineralised or denuded surfaces and resorption ensues. Tronstad refers to this type of resorption as inflammatory, which may be transient or progressive. Transient inflammatory resorption will repair with the formation of a cementum-like tissue, unless there is continuous stimulation. Transient root resorption will occur in traumatised teeth or teeth that have undergone periodontal treatment or orthodontics. Progressive resorption may occur in the presence of infection, certain systemic diseases, mechanical irritation of tissue or increased pressure in tissue.

Internal resorption

The aetiology of internal resorption is thought to be the result of a chronic pulpitis. Tronstad believes that there must be a presence of necrotic tissue in order for internal resorption to become progressive.18 In most cases, the condition is pain-free and so tends to be diagnosed during routine radiographic examination. Chronic pulpitis may follow trauma, caries or iatrogenic procedures such as tooth preparation, or the cause may be unknown. Internal resorption occurs infrequently, but may appear in any tooth; the tooth may be restored or caries-free. The defect may be located anywhere within the root canal system. When it occurs within the pulp chamber, it has been referred to as ‘pink spot’ because the enlarged pulp is visible through the crown. The typical radiographic appearance is of a smooth and rounded widening of the walls of the root canal. If untreated, the lesion is progressive and will eventually perforate the wall of the root, when the pulp will become non-vital (Fig. 7a). The destruction of dentine may be so severe that the tooth fractures.

A warm gutta-percha technique will obturate the defect fully

A warm gutta-percha technique will obturate the defect fully

The treatment for non-perforated internal resorption is to extirpate the pulp and prepare and obturate the root canal. An inter-appointment dressing of calcium hydroxide may be used and a warm gutta-percha filling technique helps to obturate the defect (Fig. 7b). The main problem is the removal of the entire pulpal contents from the area of resorption while keeping the access to a minimum. Hand instrumentation using copious amounts of sodium hypochlorite is recommended. The ultrasonic technique of root canal preparation may provide a cleaner canal as the acoustic streaming effect removes canal debris from areas inaccessible to the file. The prognosis for these teeth is good and the resorption should not recur.

The treatment of internal resorption that has perforated is more difficult, as the defect must be sealed. When the perforation is inaccessible to a surgical approach, an intracanal seal may be achieved with a warm gutta-percha technique. Alternatively, the root canal and resorbed area may be obturated using mineral trioxide aggregate. Before the final root filling is placed, a calcium hydroxide dressing is recommended.

External resorption

There are many causes of external resorption, both general and local.19 An alteration of the delicate balance between osteoblastic and osteoclastic action in the periodontal ligament will produce either a build-up of cementum on the root surface (hypercementosis) or its removal together with dentine, which is external resorption.

Resorption may be preceded by an increase in blood supply to an area adjacent to the root surface. The inflammatory process may be due to infection or tissue damage in the periodontal ligament, or, alternatively post-traumatic hyperplastic gingivitis and cases of epulis. It has been suggested that osteoclasts are derived from blood-borne monocytes. Inflammation increases the permeability of the associated capillary vessels, allowing the release of monocytes which then migrate towards the injured bone and/or root surface. Other causes of resorption include pressure, chemical, systemic diseases and endocrine disturbances.

Six different types of external resorption have been recognised and recorded in the literature.

Surface resorption

Surface resorption is a common pathological finding.20 The condition is self-limiting and undergoes spontaneous repair. The root surface shows both superficial resorption lacunae and repair with new cementum. The osteoclastic activity is a response to localised injury to the periodontal ligament or cementum. Surface resorption is rarely evident on the radiograph.

Inflammatory resorption

Inflammatory resorption is thought to be caused by infected pulp tissue. The areas affected will be around the main apical foramina and lateral canal openings. The cementum, dentine and adjacent periodontal tissues are involved, and a radiolucent area is visible radiographically. In the case illustrated in Figure 8 the root canal was sclerosed following trauma at an early age. Root planing during periodontal treatment which removed the cementum layer appeared to be the initiating factor for inflammatory resorption around a lateral canal. The root canal was identified and root canal treatment carried out, followed by external surgical repair of the lesion.

Figure 8: a) Inflammatory resorption following periodontal treatment of a tooth with a necrotic pulp.

b) Root canal treatment has been carried out, and the lesion repaired by a surgical approach

b) Root canal treatment has been carried out, and the lesion repaired by a surgical approach

Replacement resorption

Replacement resorption is a direct result of trauma and has been described in detail by Andreasen.21 A high incidence of replacement resorption follows replantation and luxation, particularly if there was delay in replacing the tooth or there was an accompanying fracture of the alveolus. The condition has also been referred to as ankylosis, because there is gradual resorption of the root, accompanied by the simultaneous replacement by bony trabeculae. Radiographically, the periodontal ligament space will be absent, the bone merging imperceptibly with the dentine.

Once started, this condition is usually irreversible, leading ultimately to the replacement of the entire root. Calcium hydroxide treatment is unlikely to help in the treatment of this type of resorption.

Pressure resorption

Pressure on a tooth can eventually cause resorption provided there is a layer of connective tissue between the two surfaces. Pressure can be caused by erupting or impacted teeth, orthodontic movement, trauma from occlusion, or pathological tissue such as a cyst or neoplasm. Resorption due to orthodontic treatment is relatively common. One report of a 5–10-year follow-up after completion of orthodontic treatment found an incidence of 28.8% of affected incisors.22

It may be assumed that the pressure exerted evokes a release of monocyte cells and the subsequent formation of osteoclasts. If the cause of the pressure is removed, the resorption will be arrested.

Systemic resorption

This may occur in a number of systemic diseases and endocrine disturbances: hyperparathyroidism, Paget’s disease, calcinosis, Gaucher’s disease and Turner’s syndrome. In addition, resorption may occur in patients following radiation therapy.

Idiopathic resorption

There are many reports of cases in which, despite investigation, no possible local or general cause has been found. The resorption may be confined to one tooth, or several may be involved. The rate of resorption varies from slow, taking place over years, to quick and aggressive, involving large amounts of tissue destruction over a few months. The site and shape of the resorption defect also varies. Two different types of idiopathic resorption have been described.

Apical resorption is usually slow and may arrest spontaneously; one or several teeth may be affected, with a gradual shortening of the root, while the root apex remains rounded. Cervical external resorption takes place in the cervical area of the tooth. The defect may form either a wide, shallow crater or, conversely, a burrowing type of resorption. This latter type has been described variously as peripheral cervical resorption, burrowing resorption, pseudo pink spot, resorption extra camerale and extracanal invasive.

There is a small defect on the external surface of the tooth; the resorption then burrows deep into the dentine with extensive tunnel-shaped ramifications. It does not, as a rule, affect the dentine and predentine in the immediate vicinity of the pulp. This type of resorption is easily mistaken for internal resorption. Cervical resorption may be caused by chronic inflammation of the periodontal ligament or by trauma. Both types of cervical resorption are best treated by surgical exposure of the resorption lacunae and removal of the granulation tissue. The resorptive defect is then shaped to receive a restoration.

The perio-endo lesion

The differential diagnosis of perio-endo lesions has become increasingly important as the demand for complicated restorative work has grown. Neither periodontic nor endodontic treatment can be considered in isolation as clinically they are closely related and this must influence the diagnosis and treatment. The influence of infected and necrotic pulp on the periapical tissues is well known, but there remains much controversy over the effect that periodontal disease could have on a vital pulp.

Examination of the anatomy of the tooth shows that there are many paths to be taken by bacteria and their toxic products between the pulp and the periodontal ligament. Apart from the main apical foramina, lateral canals exist in approximately 50% of teeth, and may be found in the furcation region of permanent molars.23 Seltzer et al. observed inter-radicular periodontal changes in dogs and monkeys after inducing pulpotomies and concluded that noxious material passed through dentinal tubules in the floor of the pulp chamber.24 In addition to dentinal tubules, microfractures are often present in teeth, allowing the passage of microorganisms. Clinically, it is common to see cervical sensitivity.

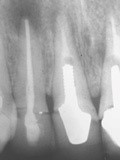

The controversy concerning the effect of periodontal disease on the pulp ranges between those who believe that pulpitis or pulp necrosis or both can occur as a result of periodontal inflammation, to those who state categorically that pulpal changes are independent of the status of the periodontium. In the author’s opinion, Belk and Gutmann present the most rational view, which is that periodontal disease may damage pulp tissue via accessory or lateral canals, but total pulpal disintegration will not occur unless all the main apical foramina are involved by bacterial plaque (Fig. 9).25

A severe endo-perio lesion that may require root resection

The problem that faces the clinician treating perio-endo lesions is to assess the extent of the disease and to decide whether the tooth or the periodontium is the primary cause. Only by carrying out a careful examination can the operator judge the prognosis and plan the treatment.26 There are several ways in which perio-endo lesions can be classified; the one given below is a slight modification of the Simon, Glick and Frank classification.27

The problem that faces the clinician treating perio-endo lesions is to assess the extent of the disease and to decide whether the tooth or the periodontium is the primary cause. Only by carrying out a careful examination can the operator judge the prognosis and plan the treatment.26 There are several ways in which perio-endo lesions can be classified; the one given below is a slight modification of the Simon, Glick and Frank classification.27

Classification of perio-endo lesions

Class 1. Primary endodontic lesion draining through the periodontal ligament

Class l lesions present as an isolated periodontal pocket or swelling beside the tooth. The patient rarely complains of pain, although there will often be a history of an acute episode. The cause of the pocket is a necrotic pulp draining through the periodontal ligament. The furcation area of both premolar and molar teeth may be involved. Diagnostically, one should suspect a pulpally induced lesion when the crestal bone levels on both the mesial and distal aspects appear normal and only the furcation shows a radiolucent area.

Class 2. Primary endodontic lesion with secondary periodontal involvement

If left untreated, the primary lesion may become secondarily involved with periodontal breakdown. A probe may encounter plaque or calculus in the pocket. The lesion will resolve partially with root canal treatment but complete repair will involve periodontal therapy.

Class 3. Primary periodontal lesions

Class 3 lesions are caused by periodontal disease gradually spreading along the root surface. The pulp, although compromised, may remain vital. However, in time there will be degenerative changes. The tooth may become mobile as the attachment apparatus and surrounding bone are destroyed, leaving deep periodontal pocketing. Perodontal disease will usually be seen elsewhere in the mouth unless there are local predisposing factors such as a severely defective restoration or proximal groove.

Class 4. Primary periodontal lesions with secondary endodontic involvement

A Class 3 lesion progresses to a Class 4 lesion with the involvement of the main apical foramina or possibly a large lateral canal. It is sometimes difficult to decide whether the lesion is primarily endodontic with secondary periodontal involvement (Class 2), or primarily periodontal with secondary endodontic involvement (Class 4), particularly in the late stages. If there is any doubt, the necrotic pulp should be removed; any improvement in the periodontal disease suggests that the classification was in fact of a Class 2 lesion.

Root removal and root canal treatment

To prevent further destruction of the periodontium in multirooted teeth, in may be necessary to remove one or occasionally two roots. As this treatment will involve root canal therapy and periodontal surgery, the operator must consider the more obvious course of treatment, which is to extract the tooth and provide some form of fixed prosthesis. As a guide, the following factors should be considered before root resection:

Functional tooth. The tooth should be a functional member of the dentition.

Root filling. It should be possible to provide root canal treatment which has a good prognosis. In other words, the root canals must be fully negotiable.

Anatomy. The roots should be separate with some inter-radicular bone so that the removal of one root will not damage the remaining root(s). Access to the tooth must be sufficient to allow the correct angulation of the handpiece to remove the root. A small mouth may contra-indicate the procedure.

Restorable. Sufficient tooth structure must remain to allow the tooth to be restored. The finishing line of the restoration must be envisaged to ensure that it will be cleansable by the patient.

Patient suitability. The patient must be a suitable candidate for the lengthy operative procedures and be able to maintain a high standard of oral cleanliness around the sectioned tooth.

A tooth that requires a root to be resected will need root canal treatment. The surgery must be planned with care, particularly with respect to the timing of the root treatment. Ideally, the tooth should be root filled prior to surgery, except for the root to be resected. The pulp is extirpated from the root to be removed, the canal widened in the coronal 2—3 mm and restored with a permanent material. This means a retrograde filling will not have to be placed at the time of surgery — a procedure which is difficult to perform owing to poor access and blood contamination of the filling and the likelihood of the restorative material falling into the socket.

Correspondence to: support@delianbj.org